Here’s something that catches thousands of cross-border taxpayers off guard every year. You earn income in India. You’re also taxed in the United States. Suddenly, you’re paying tax on the same income twice.

That’s where the US-India Income Tax Treaty comes in. It’s designed to prevent exactly this kind of double taxation. But here’s the catch. The treaty doesn’t work automatically. You need to actively claim its benefits.

Most people don’t realize this until it’s too late.

This guide will walk you through everything you need to know about the US-India DTAA (Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement). What it covers. How it protects you. And most importantly, the exact steps to claim relief.

Let’s start with the basics.

What Is a DTAA and What Does the US-India Treaty Cover?

DTAA stands for Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement.

Think of it as a contract between two countries. They agree on who gets to tax what income. And how to give relief when both countries have taxing rights.

The purpose is simple. Without these treaties, you could end up paying 30% tax in India and another 25% in the US on the same income. That’s 55% gone. Obviously unfair.

The US-India treaty solves this in two ways. First, it assigns primary taxing rights. For certain income, only one country gets to tax it. Second, when both countries can tax the same income, the treaty ensures you get credit for tax paid in one country when filing in the other.

The treaty covers most common types of income:

- Business profits

- Employment income (salaries)

- Dividends from investments

- Interest income

- Royalties and fees

- Capital gains from selling assets

- Pensions and annuities

The official treaty document runs over 40 pages. It’s dense legal text. But the core principles are straightforward once you break them down. One important thing to understand. The treaty sits above domestic tax law in most cases. If the treaty says India can only charge 15% on dividends, Indian domestic law (which might say 20%) takes a back seat. But you need to prove you’re entitled to treaty benefits. That’s where most people struggle.

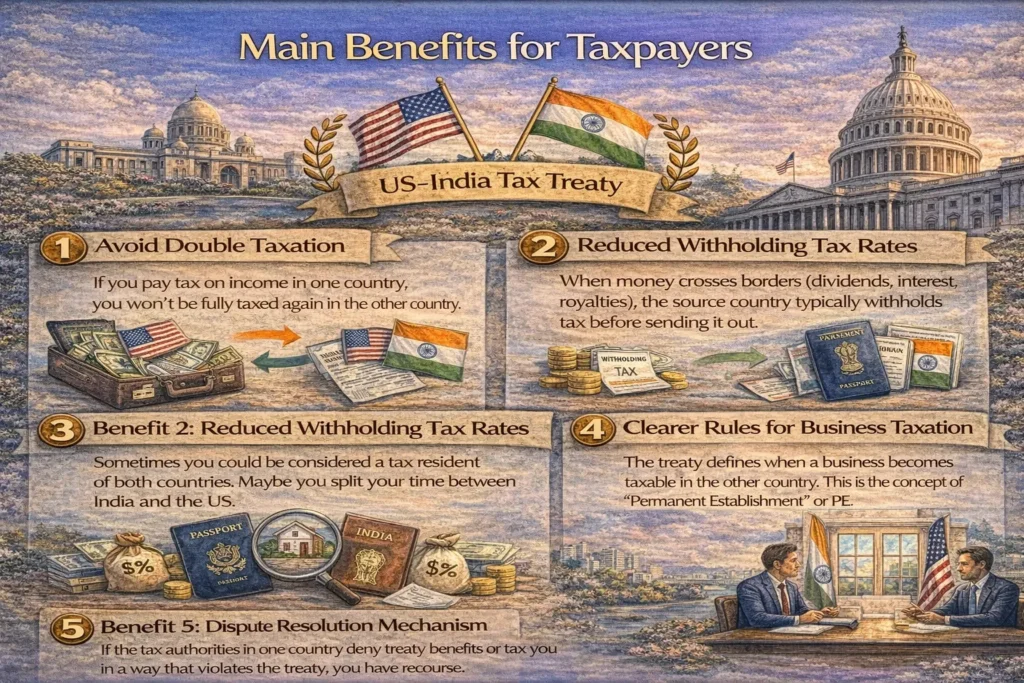

Main Benefits for Taxpayers

The US-India treaty gives you five major protections.

Benefit 1: Avoid double taxation

This is the big one. If you pay tax on income in one country, you won’t be fully taxed again on the same income in the other country. You’ll either get an exemption (no tax in the second country) or a credit (tax in the second country is reduced by what you already paid).

For example, say you earn rental income from property in India. India taxes it at 30%. When you report this income on your US return, the US allows you a foreign tax credit for the 30% you already paid. You don’t pay double.

Benefit 2: Reduced withholding tax rates

When money crosses borders (dividends, interest, royalties), the source country typically withholds tax before sending it out.

Without the treaty, these withholding rates can be brutal. India’s domestic withholding rate on dividends paid to non-residents can be 20%. On interest, it can be 30% or more.

The treaty reduces these rates. Dividends typically get capped at 15%. Interest at 10% to 15%. Royalties at 10% to 15%, depending on the type.

That’s real money saved. On a $100,000 dividend payment, you’re looking at $5,000 to $10,000 in savings.

Benefit 3: Residence tie-breaker rules

Sometimes you could be considered a tax resident of both countries. Maybe you split your time between India and the US. Or your circumstances are ambiguous.

The treaty has a tie-breaker test. It looks at where your permanent home is. Where your personal and economic ties are strongest. Where you habitually live. And as a last resort, your nationality.

This test determines your single treaty residence. You’re treated as a resident of only one country for treaty purposes. This prevents both countries from claiming full taxing rights simultaneously.

Benefit 4: Clearer rules for business taxation

The treaty defines when a business becomes taxable in the other country. This is the concept of “Permanent Establishment” or PE.

Without a PE, your business profits are only taxed in your home country. Even if you have some activity in the other country.

This is crucial for companies and consultants doing cross-border work. The PE rules tell you exactly when you cross the line from “just doing business with the other country” to “having a taxable presence there.”

Benefit 5: Dispute resolution mechanism

If the tax authorities in one country deny treaty benefits or tax you in a way that violates the treaty, you have recourse.

The treaty includes a Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP). Both countries’ tax authorities can discuss your case and reach an agreement. This prevents you from being caught in the middle of conflicting interpretations.

MAP cases take time. But they’re your safety valve when things go wrong.

Key Treaty Concepts Explained

Now let’s dig into the important technical concepts. Don’t worry. I’ll keep it simple.

Residence & Tie-Breaker Rules

The treaty only protects residents of the US or India. Not third-country residents.

So the first question is always: are you a resident for treaty purposes?

Each country has its own domestic rules for determining residence. In the US, it’s based on citizenship, green card status, or substantial presence (roughly 183 days over three years). In India, it’s based on physical presence during the financial year.

What happens if both countries consider you a resident?

The treaty’s Article 4 kicks in with the tie-breaker test. It applies this hierarchy:

Step 1: Permanent home: Where do you have a permanent home available to you? If it’s only in one country, that country wins.

Step 2: Centre of vital interests: If you have a home in both countries, where are your personal and economic ties stronger? Family, property, business interests all count.

Step 3: Habitual abode: Where do you habitually live? Where do you spend most of your time?

Step 4: Nationality: If it’s still unclear, which country are you a citizen of?

Step 5: Mutual agreement: If all else fails, the tax authorities of both countries discuss and decide.

Most cases get resolved at Step 1 or Step 2. You’re usually clearly more connected to one country than the other.

This determination matters for everything else in the treaty. Your treaty residence controls which benefits you can claim.

Permanent Establishment (PE)

This is where business taxation gets interesting.

A PE is a fixed place of business through which you carry out your business in the other country. If you have a PE, that country can tax the profits attributable to that PE.

If you don’t have a PE, your business profits are only taxed in your home country. Even if you have customers in the other country.

What counts as a PE?

Fixed place PE: An office, factory, workshop, warehouse, or construction site lasting more than 6 months (in some cases 9 months). The key is permanence and a fixed location.

Agency PE: If you have an agent in the other country who habitually concludes contracts on your behalf, that creates a PE. Even if you don’t have a physical office.

Service PE: If you provide services through employees or personnel in the other country for more than 90 days in any 12-month period, that can create a PE.

Here’s an example. You’re a US-based software company. You have customers in India who buy your product online. No PE. Your profits aren’t taxed in India.

But if you open an office in Bangalore with employees who sell and support customers, that’s a PE. India can tax the profits from that office. Or if you send consultants to India for a 6-month project, that might create a service PE. India could tax the income from that project. PE rules are complex. If you’re doing significant business in the other country, get professional advice. The stakes are high.

Source Rules and Taxing Rights

The treaty assigns taxing rights based on income type.

Business profits: Only taxed in your home country, unless you have a PE in the other country.

Employment income: Generally taxed where you perform the work. But there are exceptions if your stay is short and your employer isn’t in that country.

Dividends: The country where the company is located can withhold tax (up to treaty limits). Your home country also taxes it but gives credit for the withholding.

Interest: Similar to dividends. Source country withholding (at treaty rates) plus taxation in home country with credit.

Royalties: Source country can withhold at treaty rates. Home country taxes with credit.

Capital gains: Usually taxed in your country of residence. Except for real estate (taxed in the country where the property is located) and sometimes shares in real estate companies.

The treaty specifies exactly which country gets primary, secondary, or exclusive taxing rights for each income type.

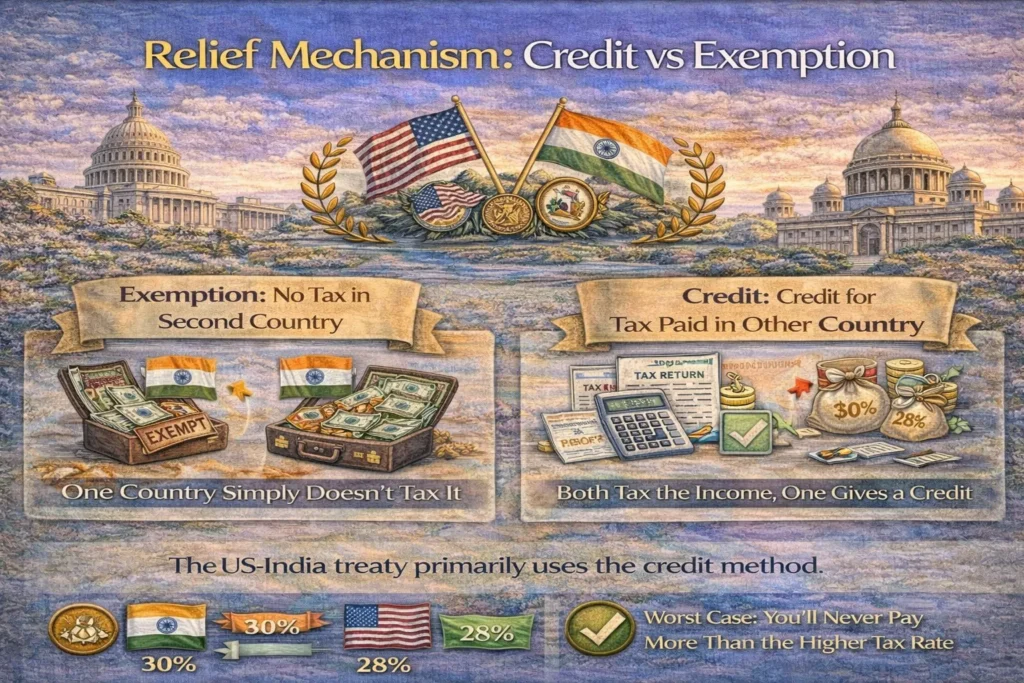

Relief Mechanism: Credit vs Exemption

When both countries can tax the same income, the treaty ensures you don’t pay double.

There are two methods:

Exemption method: One country simply doesn’t tax that income at all. It’s completely exempt.

Credit method: Both countries tax the income, but one gives you a credit for tax paid in the other country.

The US-India treaty primarily uses the credit method.

Here’s how it works. Say you earn rental income in India. India taxes it at 30%. When you report this on your US tax return, the US calculates its tax on that income. Let’s say it comes to 28%. The US gives you a credit for the 30% you paid to India. Result: you don’t pay any additional US tax on that income.

If the US tax came to 35%, you’d get a credit for 30% (what you paid India). You’d pay the remaining 5% to the US. The credit ensures you never pay more than the higher of the two countries’ tax rates. Not the sum of both rates.

India also uses the credit method for foreign taxes paid by Indian residents on foreign income. The key is documentation. You need to prove you paid tax in the other country to claim the credit. Form 26AS in India and foreign tax credit forms in the US are essential.

Typical Withholding Rates Under the India-US Treaty

Let’s talk real numbers.

The treaty caps withholding rates on cross-border payments. Here’s what you can typically expect:

| Income Type | Treaty Maximum Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dividends | 15% | Sometimes 25% if ownership is below 10% |

| Interest | 10% to 15% | Bank interest may be exempt in certain cases |

| Royalties (equipment) | 10% | For use of industrial, commercial, or scientific equipment |

| Royalties (other) | 15% | Copyrights, patents, trademarks, etc. |

| Fees for technical services | 10% to 15% | Depends on service type and treaty article |

| Capital gains | Generally 0% | Taxed in residence country, except real estate |

These are maximum rates. The actual rate can be lower if domestic law provides a lower rate.

Important caveat. These rates apply only if you qualify as the “beneficial owner” of the income. You can’t use a shell company in one country just to access treaty benefits. There are substance requirements and anti-avoidance rules.

Also, these rates are from the current treaty. Treaties get amended. Always verify the current provisions before relying on these numbers for actual tax planning.

The treaty text is publicly available. Check it whenever you’re dealing with significant cross-border income.

How Taxpayers Actually Claim Treaty Benefits

Here’s where theory meets practice.

The treaty exists. Great. But tax authorities won’t just apply treaty rates automatically. You need to claim them. And provide proof.

Let me break down the process for the two most common situations.

Non-Residents Receiving India-Source Income

You’re a US resident. You receive dividends, interest, or royalties from India.

Without the treaty, India will withhold tax at the high domestic rate. To get the reduced treaty rate, follow these steps:

Step 1: Obtain a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC)

This is your proof that you’re a US tax resident.

In the US, this means getting Form 6166 from the IRS. To get Form 6166, you first file Form 8802 with the IRS.

Form 8802 is your application for the certificate. You provide your details, the period you need certification for, and the reason (treaty benefits). The IRS reviews it and issues Form 6166 if you qualify.

Here’s the catch. Form 8802 processing takes time. Six to eight weeks is typical. Sometimes longer during busy periods.

Plan ahead. Don’t wait until the week before you need to claim treaty benefits.

Step 2: Submit TRC and Form 10F to the Indian payer

Form 10F is an Indian tax form. It’s your self-declaration of tax residency details. You fill it out with information from your TRC.

You submit both documents to whoever is paying you the income. Could be a company paying dividends. A bank paying interest. A licensee paying royalties.

The payer needs these documents before they can apply the reduced treaty withholding rate. If you don’t provide them, they’ll withhold at the higher domestic rate.

Some payers ask for these documents well in advance. Others are more flexible. But you need to provide them eventually to get treaty benefits.

Step 3: File your US tax return and claim foreign tax credit

Even though India withheld at the reduced treaty rate, you still need to report this income on your US return.

The US taxes your worldwide income. But you get a credit for the tax withheld in India.

Use Form 1116 to claim the foreign tax credit. You’ll need to provide details of the foreign income and taxes paid.

Keep all documentation. The IRS might ask for proof during an audit.

Indian Residents with US-Source Income

The process works similarly in reverse.

If you’re an Indian resident receiving US dividends or interest, you need:

A TRC from India. Apply through the Indian income tax department. This is quicker than the US process, usually takes 2-3 weeks.

US tax forms as required. If you’re receiving dividends from a US company, you’ll likely need to submit Form W-8BEN. This is the US equivalent of Form 10F. It declares your foreign status and treaty eligibility.

Documentation to support treaty claims. The US payer might ask for additional proof of your Indian residency and beneficial ownership.

Then, when filing your Indian ITR, you report the US income and claim foreign tax credit for any US tax withheld.

Corporate Taxpayers and PE Situations

For businesses, the process is more complex.

You need to establish:

Your tax residency. Via TRC from your home country.

PE status. Document why you don’t have a PE in the other country (if that’s your position). Or if you do have a PE, calculate attributable profits correctly.

Transfer pricing compliance. If you have related-party transactions, you need transfer pricing documentation to prove arm’s length pricing.

MAP filing if needed. If tax authorities deny treaty benefits or create double taxation, consider filing for Mutual Agreement Procedure.

Corporate treaty claims often involve significant amounts. Professional tax advice is essential. Don’t DIY this part.

When Relief Is Denied: Appeals, MAP & Dispute Resolution

Sometimes things go wrong.

Maybe the Indian tax authority denies your treaty claim. Or the US doesn’t give you full credit for Indian taxes. Or both countries tax the same income in ways that don’t match the treaty.

You have options.

Option 1: Administrative review or appeal

In India, if your treaty claim is denied, you can file an appeal with the Commissioner of Income Tax (Appeals). Explain why you qualify for treaty benefits. Provide all supporting documents.

In the US, if the IRS denies your foreign tax credit or treaty position, you can request an appeal within the IRS. Or eventually go to Tax Court if needed.

Option 2: Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP)

This is the nuclear option. And it’s powerful.

MAP is built into the treaty. If you believe you’re being taxed contrary to the treaty, you can ask your home country’s tax authority to initiate MAP.

The tax authorities of both countries then discuss your case. They work together to resolve the double taxation or treaty interpretation dispute.

MAP is typically used for:

- Transfer pricing disputes

- PE attribution issues

- Dual residence situations

- Complex business income allocation

The process takes time. Often 2-3 years. But it’s binding once both countries reach agreement.

To initiate MAP:

- File a written request with your home country’s competent authority (in India, the Central Board of Direct Taxes; in the US, the IRS)

- Provide full details of the issue, why it violates the treaty, and what relief you’re seeking

- Be prepared to provide extensive documentation

MAP is resource-intensive. It makes sense for significant amounts (usually at least $100,000 in disputed tax).

For smaller amounts, administrative appeals are more practical.

FAQs

Does the treaty automatically give me lower withholding rates on Indian dividends?

No. You must provide your Tax Residency Certificate (Form 6166 for US residents) and Form 10F to the Indian payer before they can apply the treaty rate. Without these documents, they’ll withhold at the higher domestic rate.

How long does it take to get Form 6166?

Plan for 6-8 weeks after filing Form 8802 with the IRS. Processing times vary. During peak periods, it can take longer. Always apply well in advance of when you need it.

Can a US citizen living in India be taxed on US income?

Generally, US citizens are taxed on worldwide income regardless of where they live. The treaty doesn’t change this. However, you may be able to claim foreign tax credits for Indian taxes paid, or in some cases use the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion for US employment income.

What happens if I’m a tax resident of both countries?

The treaty’s tie-breaker rules (Article 4) determine your single treaty residence based on permanent home, centre of vital interests, habitual abode, and nationality. This prevents both countries from claiming you’re solely their resident for treaty purposes.

Do I need to file tax returns in both countries?

Possibly. The US taxes its citizens and residents on worldwide income, requiring a US return. India taxes residents on worldwide income and non-residents on India-source income. Whether you need to file in each country depends on your residency status and income sources in each location.

Can I get a refund if too much tax was withheld?

Yes. File a tax return in the country that over-withheld. In India, file the appropriate ITR form showing the TDS withheld and claim the excess as a refund. In the US, file Form 1040-NR if you’re a non-resident or Form 1040 if you’re a US taxpayer.

What if the treaty and domestic law conflict?

Generally, treaty provisions override domestic law when they’re more favorable. But there are anti-avoidance provisions and some domestic law limitations that can apply. The interplay can be complex, so consult a tax professional for significant amounts.

How do I prove beneficial ownership?

Provide documentation showing you have the rights to use and enjoy the income. This includes bank statements in your name, shareholder certificates, custody account statements, and explanations of the economic substance of your ownership. Avoid structures where you’re merely a nominee.

0 Comments